I’ve been interested in photography from a really early age, and here is why it happened.

The Wheaties camera

I first got interested in taking pictures when I found I could get an actual working camera for 55 cents and a Wheaties boxtop. I was about 7 years old and this was pretty exciting for me. Mine used 127 film which you then “took to the drugstore” to have processed. You got back little contact prints about 1” x 1.5”. I’m not sure if enlargements were yet available, but enlargements from such a cheap camera would have been pretty awful. Some years later, I actually had a summer job at the local photofinisher that serviced all those drugstores. But that’s another story.

These promotional cameras were made by Regal Galter of Chicago, and were available with various nameplates. While they were little more than toys, they did take actual pictures and I took a lot of pictures, especially on vacation or when we took visitors to nearby Niagara Falls.

This was really a learning experience, and I am sure most of my pictures were terrible, but every mistake led to more chances to learn. Of course, the camera had no settings for shutter speed or lens opening. And, in those days, the only 127 film type was Kodak Verichrome Pan, a very forgiving, wide latitude film that produced reasonable pictures over a wide variety of lighting conditions. This was, of course, an outdoor, daylight camera. Inside shots and flash pictures were still in the future.

The Brownie Hawkeye

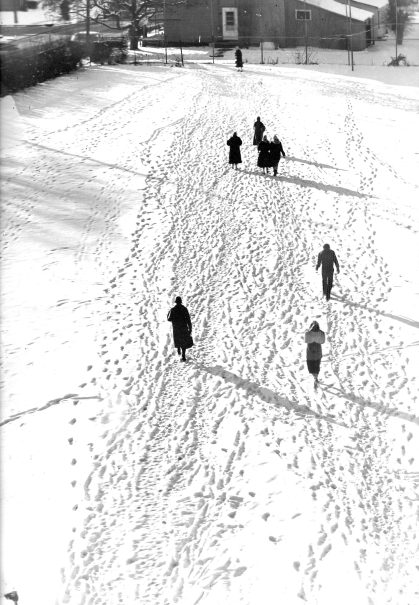

|

|

When I was about 11, and in about 6th grade, my parents surprised me with a wonderful new camera, the Kodak Brownie Hawkeye. It used 620 film, producing negatives that were 2 ¼ x 2 ¼ inches (or 6 x 6 cm). The bakelite Brownie had a bright prism waist-level viewfinder, and there were a number of types of film available for it, including Verichrome Pan, Tri-X and Kodacolor. The flash attachment used flashbulbs, of course, and while you could use ordinary white flahsbulbs you could get blue flashbulbs to simulate the outdoor color balance for outdoor Kodacolor. (Color film came in outdoor and incandescent in those days.) Contact prints from these 2 ¼” square negatives were decent sized, and the camera quality was sufficient to stand enlargement to “oversize” prints if you wanted to pay for it.

The Brownie Hawkeye was made from 1949-1961, with the flash model introduced in 1950. It was the most popular Brownie ever made, and you can still find them around pretty easily. They make good stage props and there was a recent men’s clothing ad where the model was using a Brownie Hawkeye, but was foolishly holding it up to his eye! The original Brownie Hawkeye cost $5.50 and the flash model $7.00!

This Brownie went with me on all our vacations and I even got to take it to school on occasion to snap pictures of my friends.

As I moved on into Junior High School, I became interested in developing and printing my own pictures, and the 620 film was easy to handle and contact print. I developed the film in a little plastic tank using Microdol-X or D-76 and contact printed the negatives. It was clearly time for an upgrade.

My Yashica was my first medium format camera

In about eighth grade, I bought a Yashica (probably using my paper route money): a pretty good quality twin lens reflex, using 120 film and still making 2 ¼” square negatives. The Yashica had a f 2.8 viewing lens which projected onto a ground glass screen for focusing, and a f/3.5 taking lens. This was my first camera that allowed focusing, as well as setting of the lens opening and shutter speed. This was a huge learning experience, and it was a good thing I could develop the film myself, because I ran through a lot of getting the hang of setting the exposure correctly. I used the Brockway incident light meter as well. And it was the first camera with decent resolution that allowed good enlargements.

The two knobs on the front controlled the lens opening and shutter speed, and the large knob on the side moved the two lenses in and out for focusing. The rear knob was for advancing the film. I don’t think there was an interlock to prevent double exposures, though. And there was no film advance that assured that you moved the film far enough. You had to look at the numbers on the back of the film paper that were displayed in the window on the back of the camera.

Around this same time, a took possession of a used enlarger much like the Kodak enlarger shown here, which really opening my vistas to making contact sheets, and making small enlargements on Kodak Medalist paper, developed in Dektol. This enlarger was a diffusion model, where the enlarger lamp is diffused through ground glass and passed through the negative and then to the enlarger lens.

That Yashica was my main camera throughout high school. I used it for sports photography and group photos of all kinds.

Ventures into 35mm

Around this time, 1957 or so, 35mm cameras were getting better and cheaper and my father bought me a Minolta 35mm camera. I was soon taking so many candid pictures with it that I started spooling my own bulk film into 35mm cassettes. In those days, you could reuse standard Kodak cartridges, but Kodak put an end to that in about 1964 by crimping the ends so you had to use a bottle opening to pull them open.

Around this time, 1957 or so, 35mm cameras were getting better and cheaper and my father bought me a Minolta 35mm camera. I was soon taking so many candid pictures with it that I started spooling my own bulk film into 35mm cassettes. In those days, you could reuse standard Kodak cartridges, but Kodak put an end to that in about 1964 by crimping the ends so you had to use a bottle opening to pull them open.

The Minolta was only my second adjustable camera, where I took light meter readings and set the camera accordingly. The camera was well built, and I used it throughout high school for all my candid work for the yearbook. It did not feature interchangeable lenses, however.

It also introduced the possibility of color slides, which I dived into as well. And in fact, it turns out you can process your own Ektachrome, and I did that for some years to save money and for instant gratification. During high school, my friend Jeff Luce and I did some color film processing and printing (from 2 ¼” square negatives) It was a lot of fun, but took an awful lot of work. This did, however, give us a chance to crop and adjust the darkness if our photos.

This was also about the time that I switched to the Nikor stainless steel film processing tanks that I still have and use. It takes a little practice to load them, but once you get the hang of it, they are very easy to load in the dark or even in a changing bag. This is probably now one of photography’s great lost skills! Sadly these tanks are no longer made, although other vendors have similar models.

The Kodak Retina

Around the start of the senior year in high school, the Minolta was not all it could be, and I looked around for a camera with sharper optics. I settled on the rather unique Kodak Retina IIc, a German made camera with an f/3.5 Schneider Xenon lens, and shutter speeds to 1/500th. It had a built in light meter and introduced (to me at least) the LVS or Light Value System, later called the EV or exposure Value system.

You matched a pointer to the light meter needle on the top of the camera, and that gave you a single LVS number. You set that LVS number on a wheel at the bottom of the lens, and it locked together all the f/stops and shutter speed combinations that would give you that exposure.

The Retina had a very sharp lens, rivalling the Nikons I later went to. While there were two additional lenses available: wide angle and short telephoto, they only replaced the front elements, not the whole lens and I never looked into them.

Later on that year, my father bought a Retina IIIc, which was the same camera with a f/2 lens, and that is the one pictured here. It still works very well.

I used the Retina IIc all through the rest of high school and nearly all of college as my camera for candids, and having joined the yearbook staff right away, I had access to a very good darkroom.

My Rolleiflex

In early January of my Senior year in high school, a friend of mine who worked at a local photo store called me to say that a used Rolleiflex had just come in that was in immaculate condition and I ought to get it immediately. My father worked near there and I called and asked him to take a look. He told me it had been sold, but didn’t tell me that he’d bought it for my birthday.

This was one highest quality cameras I’d ever had. It had a f/2,8 viewing lens and an f/3.5 taking lens and a film transport system that assured that the roll would always be advanced the correct amount. I used this all through my college career along with the Retina. And I had that camera for 40 years after that. It took outstanding photos.

Moving on to Nikons

In my senior year in college, I wanted to move on to a camera with interchangeable lenses and high quality optics. Selling my Retina combined with a small early graduation present, I put together enough money to either buy a Nikon F or a Nikkorex F plus a Sigma 60mm-200mm zoom lens. They were about the same price. The Nikon F was a thoroughly professional-grade camera of its time, and the NIkkorex was intended for the amateur market. It had excellent Nikon optics but instead of the usual focal plane shutter, had a Copal Square metal blade shutter. I chose the latter because it seemed like a bargain to an impecunious college student.

When I got the Nikkorex, I found that that shutter was hardly silent and was roughly as noisy as a bear trap. Just the thing for shooting wedding ceremonies! Much later, I learned that this Nikkorex was sort of a joint project between Nikon and Mamiya, who actually manufactured the camera. That model was later sold by Ricoh, and Nikon went on to produce a number of Nikkormat cameras for the amateur market.

What can I say? It may not have been top of the line, but I used that Nikkorex all through graduate school and while raising a young family. It may have been a bit noisy, but the optical quality was very good.

Finally, a real Nikon

While teaching at Tufts, I wrote a number of books, and the royalties from my first book and second book enabled me to finally trade my Nikkorex in for a Nikon F3, one of Nikon’s most popular film cameras of all time. Of course, the Sigma zoom lens worked with the new Nikon just fine. I also managed to buy a new Beseler 23 C enlarger.

This Nikon F3 that I bought in 1980 was a workhorse camera for me for years: I didn’t seek to upgrade until digital cameras became more common in the early 2000s. I still have it and it works just as well as the day I got it.

Replacing the Rollei

By the early 2000s, my Rolleiflex was showing the signs of age. It just didn’t produce as sharp images as it once did, and it seemed ill-advised to spent money on repairing a 40 or more year old camera that was no longer made, so I sold it and bought a used single lens reflex Rollei 6008. This is a battery driven camera with through the lens metering and interchangeable 120 (or 220) film magazines, so you could switch from black and white to color, or between different film speeds mid-roll. The film advance was automatic, and while there were other lenses available for it, their prices were astronomical.

I took some photos with it recently and it remains an amazing machine: solidly build with incredible resolution. It is not autofocus, although Rollei did make a model that was at some exorbitant price. The producers of the Rollei line, Frank & Heidecke, went out of business in 2009 and Rolleis are no longer being produced, although there are a large number in the used market.

Frankly, this is a camera that only a tripod can love, since with the hand grip it weighs 79 oz or nearly 5 lbs. Its images are unsurpassed, however.

My journey into digital cameras

In 2001, digital cameras became price accessible, although still of just moderate quality. My first digital camera was the Nikon e995 Coolpix which was really only suitable for making small pictures for a web site, with e megapixel resolution (2048 x 1536). Nonetheless, it was good for closeups and I used it for about 3 years.

The Nikon D70

This was a 6 megapixel camera (2000 x 3008) that stood me in good stead for 4 years. It had a good zoom lens (18-70mm f/3.5-5.6) that was considerably more light sensitive than the previous Coolpix, and the lenses were interchangeable. I soon got a telephoto zoom(70mm-300mm) for it as well. And with that resolution, I could take good quality stage pictures easily.

The Nikon D80

Four years later, I upgraded to the Nikon D80 to further improve resolution to 10 mexapixels (3872×2592), but kept the same lenses. This workhorse camera stood me in good stead for tens of thousands of pictures of all kinds. It was the first one that I felt I could make decent enlargements from and many of those are still hanging around our house.

Nikon D7200

I finally moved to a Nikon D7200 (24 megapixels) in 2017 and with it a new kit zoom lens, since the one I used with the D70 and D80 needed replacement from heavy use. But the 70-300mm telephoto remained in happy use. This was the first camera I’d had that would also do movies. It was a handy feature but I personally didn’t use it all that often. But the higher resolution was a great boon for landscape photography as well as stage photography.

The Nikon Z6

You would think that this should be the end of the story, but all of those digital cameras above used a 24 x 16 mm sensor, called DX format, while a full frame sensor would be 24 x 36 mm, or FX format. These full frame sensors can have the same number of pixels as the DX cameras and produce a much sharper image.

This year, Nikon introduced the Z6 (and Z7) cameras which had a full frame sensor and 24 megapixels (or 45 for the Z7). It is also a mirrorless camera that reduces vibration as well as the shutter sound since there is no mirror to flip out of the way. It has gotten very good reviews, included one I wrote comparing it to the D7200. However, Nikon also introduced a new Z lens mount and an accompanying adapter for recent older lenses, while they develop new Z-mount lenses.

This is simply the sharpest camera of any kind I have ever had, and an absolute joy to use. I haven’t been on any picturesque vacations yet using the Z6, but here is a lovely local picture that shows its sharpness.

Conclusions

I wouldn’t be the photographer I’ve become without all those experiences, and starting at a young age was part of it. Only that way do you become entranced with the magic of film, seeing the prints and learning what works. And the magic of seeing prints develop in a darkroom tray is a thrill that few experience any more.

It’s easy to carry around your digital camera and never download or print any of those pictures, but that is a big mistake. The reward of beautiful prints is worth a little effort and is a big part of the learning experience that can make you a better photographer.

To some extent having a little digital camera in your phone bypasses all these steps and make photography seem routine. Again, starting young is still a step on the way to build confidence in your creativity and you should do your best to encourage young people to do more than take snapshots. And they should make some prints, too!